The protocol for Meningitis:

Meningitis2

Let’s break it down!

Meningitis is defined as an inflammation of the meninges, which are layered tissues surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Although meningitis is most commonly caused by viruses, it’s the bacterial infections that we’re most worried about, which carries a mortality of up to 30%.

Overall, the incidence of meningitis has decreased since the introduction of vaccines that cover the most common pathogens like Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Haemophilus influenzae. In developed countries, vaccination has nearly eliminated the risk of Haemophilus influenzae meningitis.

In developed countries like the US, the incidence is only 0.6 – 4 cases per 100,000 adults. But in resource-poor countries, the incidence can be as high as 1,000 cases per 100,000 adults. Any deployments or travel to exotic places where pest control and sewage are questionable increases the risk of acquiring and disseminating the disease.

For more on the pathophysiology of meningitis, check out the video below:

The gold standard for diagnosing meningitis is to do a lumbar puncture and examine the cerebral spinal fluid for pathogens. However, it’s not likely that you’ll have this capability. A diagnosis can be made clinically by looking for the classic “meningitis triad”:

1. Headache (84%): The most common symptom; severe headache with a rapid onset that can be felt across the entire head.

2. Fever (74%): Will be at least 38°C or 100.4°F

3. Neck Stiffness (74%): Also known as “Nuchal Rigidity“. Patients may describe this, but this can also be tested through tests that stretch the meninges, such as Brudzinski’s sign and Kernig’s sign. The videos below show how to perform them

The triad is very helpful, but it’s not definitive. It only occurs in about 50% of all bacterial meningitis patients. Some other symptoms that you can look for include photophobia (sensitivity to light), malaise (feeling of discomfort); seizures; or nausea (occurs in 62% of patients)

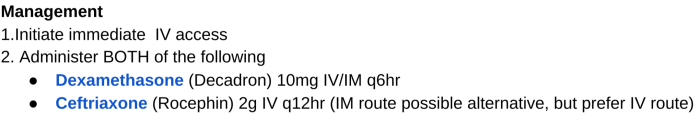

1. Initiate immediate IV access

The first step will be to initiate intravenous access so that we can rapidly administer antibiotics, steroids, etc.

2. Administer BOTH of the following: Dexamethasone and Ceftriaxone

Dexamethasone is a glucocorticoid that is used for its strong anti-inflammatory properties. However, the use of steroids is controversial in patients for meningitis. Studies have shown that it may reduce mortality, hearing loss, and other neurological complications, but it only has any benefit for pneumococcal meningitis and it’s only beneficial if given prior to antibiotics.

Ceftriaxone is a powerful third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic that covers a broad spectrum of bacterial. Ceftriaxone has consistent (CSF) penetration and potent activity against the major pathogens of bacterial meningitis, with the notable exceptions of L. monocytogenes and some penicillin-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae. This is is the primary treatment for meningitis that can’t be ignored.

3. Treat per Pain Management protocol

Meningitis patients will suffer from remarkable head/neck pain that may need to be managed. NSAIDs and Tylenol are appropriate, with the potential for using opiates like Morphine or Fentanyl. However, caution should be exercised when considering narcotics in severely hypotensive patients.

4. Treat per Nausea/Vomiting protocol

Nausea occurs in 62% of meningitis patients. The best drugs from the Nausea/Vomiting protocol for these patients will likely be Ondansetron (Zofran) or Promethazine (Phenergan).

5. If seizures occur, treat per Seizure protocol

Seizures are uncommon but still occur in about 23% of meningitis patients. These will still be treated just like any other seizure with airway management and benzodiazepines like Diazepam or Midazolam

Post-exposure prophylaxis is indicated for individuals who have been in close contact for >8 h or had exposure to oral secretions of patients diagnosed with Neisseria meningitides. One brief dose from broad-spectrum antibiotics like Moxifloxacin and Ceftriaxone is usually enough to prevent infection.

Meningitis is no joke. In addition to the 30% mortality, 28% of bacterial meningitis patients will suffer from long-term neurological complications. If you have a patient that you suspect of having meningitis, they will need additional testing and therapies that you won’t be able to provide in the field. Thus, an Urgent evacuation is warranted

Good luck out there!

References

- UpToDate: Clinical features and diagnosis of acute bacterial meningitis in adults

- UpToDate: Initial therapy and prognosis of bacterial meningitis in adults

- EMRAP Corependium: Central Nervous System Infection

- Advanced Tactical Paramedic Protocols Handbook. 10th ed., Breakaway Media LLC, 2016.

- Why every medic should love Deployed Medicine - November 8, 2020

- 3 Areas Where Medics Fall Short - November 7, 2020